Baptism

SERGEY TROSTYANSKIY

Baptism is the first sacrament of the Orthodox Church. In the Early Christian centuries this mystery was known under various names, including “the washing of regeneration,” Illumination (photismos) and “the sacrament of water.” In Christianity baptism is also considered the most important sacrament of the church, as it initiates one into mystical communion with Christ. Therefore, it is also called “the door” that leads peoples into the Christian Church. Baptism completely releases the believer from ancestral sin and personal sins committed up until that time. It is rebirth into new life, justification, and restoration of communion with God.

The theological significance of baptism in Orthodox Christianity is summed up in its primary sacramental symbols: water, oil, and sacred chrism. As Fr. Alexander Schmemann noted, water is the most ancient and universal of religious symbols. It has multiple, in some cases contradictory, scriptural significations attached to it. On the one hand, it is the principle of life, the primal matter of the world, a biblical symbol of the Divine Spirit (Jn. 4.10–14; 7.38–39); on the other, it is a symbol of destruction and death (the Flood, the drowning of the pharaoh), and of the irrational and demonic powers of the world (as in the icon of Jesus’ baptism in the river Jordan). Sacramentally, the use of water symbolizes purification, regeneration, and renewal. It has an extraordinary significance in the Creation narrative of the Old Testament, and is also a key symbol in the Exodus story. In the New Testament it is associated with St. John the Baptist and his washing of repentance and forgiveness. These three biblical types are combined powerfully in the Orthodox ritual of baptism.

In Christianity water became a symbol that incorporated the entire content of the Christian faith. It stands for creation, fall, redemption, life, death, and resurrection. St. Paul the Apostle in his Epistle to the Romans (6.3–11) gives a foundational account of this mystical symbolism. St. Cyril of Jerusalem, in his 4th-century homilies on the “awe-inspiring rites of initiation” (Mystagogic Catecheses) described what takes place during baptism as “an iconic imitation” of Christ’s sufferings, death, and resurrection that constitutes our true salvation. Thus, here a believer dies and rises again “after the pattern” of Christ's death and resurrection. Death symbolizes sin, rejection of God, and the break of communion with God. Christ, however, destroyed death by removing sin and corruption. Here death becomes a passage into communion, love, and joy. Baptism dispenses divine grace which is given in the Spirit to humankind through Christ’s mediation.

From Antiquity the rite of baptism started with lengthy preparations (shortened in later times when infant baptism became a norm). The first preparatory step was enrollment, an inscription of the catechumen’s name in the registration book of the local church. It signified that Christ took possession over this catechumen, and now included his or her name in “the book of life.” The next step was exorcism, a serious and solemn set of rituals which were meant to liberate the catechumen from demonic powers and to restore his or her freedom. The catechumen renounced Satan.

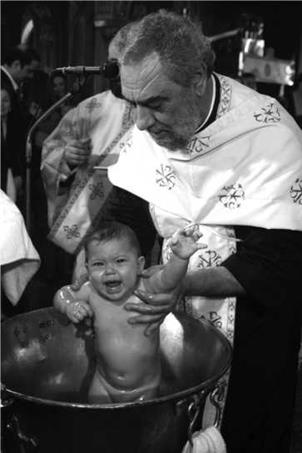

Plate 8 Baptism of a baby. Aristidis Vafeiadakis/ Alamy.

In the ritual today they still turn to the West, the symbolic dominion of Satan, and spit lifting up hands to appeal to God. Then the catechumen turns to the East, which symbolizes reorientation to the Paradise offered through Christ, and bows down, keeping the hands lowered to indicate surrender and submission. The priest then repeatedly asks the catechumen to confirm that he or she is united to Christ and believes in him as God. The catechumen confirms an unconditional commitment, faithfulness to Christ, and recites the Niceno-Constantinopolitan creed. At this point baptism itself begins with a solemn blessing of the waters. There are several elements of Orthodox Baptism: the anointing of the catechumen with blessed oil, the triple immersion in the sanctified water, the simultaneous baptismal formula of the invocation of the divine names of the Holy Trinity, and the “completion” of the water baptism with the “Seal of the Holy Spirit” in the Chrismation of the candidate with consecrated myron. The candidate is robed in white (the original meaning of the word candidatus) after the immersion, and their hair is cut (tonsured) as a sign of their vow (dedication to God). The ritual blessing of water starts with the solemn doxology: “Blessed is the Kingdom of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.” Then a long litany follows: “that this water may be sanctified with the power and effectual operation and the descent of the Holy Spirit.” The power of the Holy Spirit visible through the sacrament is understood to recreate the fallen world, symbolized by the water, transforming it into the waters of redemption. Baptism makes the catechumen a partaker of the Kingdom of God through their sharing in the death and resurrection of Christ: their mystical embodiment with him. Through the blessing, the water of creation, corrupted by the Fall, now turns into the water of Jordan, the water of sanctification, the remission of sins, and salvation. Then the baptismal water is anointed by the pouring in of blessed oil which here symbolizes healing, joy, and reconciliation. The triple immersion follows, symbolizing the three-day burial and resurrection of Christ, and the passing of the Israelites through the Red Sea, which is always performed in the name of the Holy Trinity. There are certain exceptions to this strict rule of immersion; for instance, those who are sick can be baptized by aspersion – that is, they have water poured over their heads – but this is never relaxed so as to become a standard alternative form in Orthodoxy.

The early church described another type of baptism when the catechumens were persecuted and suffered martyrdom in the name of Christ before their formal initiation. Those martyrs were said to have been admitted to Paradise by the baptism of blood. In the early Christian centuries most Christian catechumens were baptized in their adulthood. In the 4th century the fathers (such as St. Gregory the Theologian preaching Orations on the Lights in Constantinople in 380) had to encourage people not to leave their baptism until their deathbeds. Nevertheless, the baptism of infants was justified by all the early fathers. In 253 the Council of Carthage made it a recommended practice of the church. Baptism is never repeated. If a convert wishes to enter the Orthodox Church from another Christian communion it is the majority practice of the Greek and Russian traditions to chrismate a believer who has already been baptized by threefold washing in the name of the Trinity. If there is doubt over the form of liturgy that had been used, or if the convert is coming from no church background, the full service of baptism is always performed.

SEE ALSO: Catechumens; Chrismation; Exorcism; Grace; Holy Spirit; Mystery (Sacrament); Original Sin

REFERENCES AND SUGGESTED READINGS

Cyril of Jerusalem, St. (2008) The Holy Sacraments of Baptism, Chrismation and Holy Communion: The Five Mystagogical Catechisms of St. Cyril of Jerusalem. Rollinsford, NH: Orthodox Research Institute.

McGuckin, J. A. (2008) The Orthodox Church: An Introduction to Its History, Doctrine, and Spiritual Practices. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 277–88.

Sava-Popa, G. (1994) Le Bapteme dans la tradition orthodoxe et ses implications wcumeniques. Fribourg: Editions Universitaires, Schmemann, A. (1964) For the Life of the World.

New York: National Student Christian Federation. Schmemann, A. (1974) Of Water and the Spirit. Crestwood, NY. St.Vladimir’s Seminary Press.