Phelonion

PHILIP ZYMARIS

A Byzantine vestment equivalent to the western chausible. It has its origins in a poncho-like garment referred to by St. Paul (2Tim. 4.13). It was once worn by bishops but was later replaced by the sakkos. Presently, priests wear them at all sacramental services.

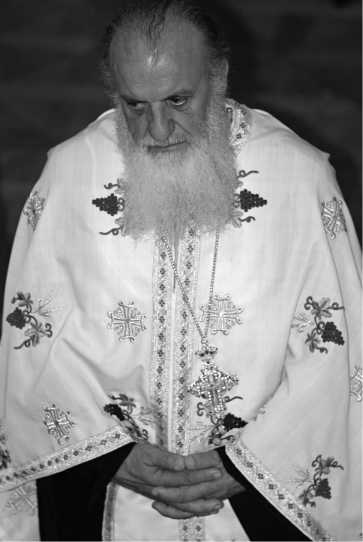

Plate 49 Orthodox priest wearing the phelonion vestment and the pectoral cross (stavrophore). PhotoEdit/Alamy.

SEE ALSO: Epitrachelion; Sticharion; Vestments

REFERENCES AND SUGGESTED READINGS

Day, P. (1993) “Phelonion,” in The Liturgical Dictionary of Eastern Christianity. Collegeville: Liturgical Press, p. 233.

Phountoulis, I. (2002) “Paradose kai exelixe leitourgikon hieron amphion,” in Ta hiera amphia kai he exoterike eribole tou orthodoxou klerou. Athens: Church of Greece Publications, pp. 63–78.

Philokalia

ANDREW LOUTH

Philokalia is the Greek term for an anthology. Nowadays, the Philokalia virtually invariably refers to a collection of Byzantine ascetical and mystical texts published in Venice in 1782 by St. Macarius of Corinth and St. Nikodemos of the Holy Mountain, although there is another famous Philokalia, of extracts from Origen, mostly on the problem of free will and the interpretation of the Scriptures, composed 358–9 by St. Basil the Great and St. Gregory of Nazianzus. The 18th-century Philokalia is a collection of texts from the 4th to the 14th centuries, culminating in works drawn from St. Gregory Palamas and his circle, both predecessors and followers, representing “hesychasm,” the monastic movement centered on the recitation of the Jesus Prayer which claimed that it was possible to behold the uncreated light of the Godhead in prayer. This claim was reconciled with the apophatic doctrine of God’s unknowability by the distinction drawn by Gregory, based on earlier Greek patristic writings, between God’s essence, which is indeed unknowable, and his uncreated (and therefore divine) “energies” or activities (energeiai in Greek) through which God makes himself known personally in the created world.

The texts in the Philokalia present a historical sequence of Byzantine ascetical texts, presented as the historical tradition leading up to Palamite hesychasm, but there is very little in them about the Jesus Prayer, and even less about the essence-energies distinction (the historical arrangement is probably due to St. Nikodemos, who had imbibed from the West a sense of history). Pride of place is given to St. Maximos the Confessor, Peter ofDamascus, and St. Gregory Palamas himself, but many other important Byzantine ascetical writers are present, including Evagrios (both under his own name and that of Neilos), Mark the Monk, Diadochos of Photiki, John of Karpathos, Niketas Stethatos, and St. Gregory of Sinai. There are some, at first sight, surprising omissions: notably St. John of Sinai, author of the Ladder of Divine Ascent, and St. Symeon the New Theologian, who is represented by a few, unrepresentative, and even spurious, writings. St. John of Sinai is probably omitted because he was already well known in the Byzantine monastic tradition, his Ladder being read in the course of each Lent. The poor showing of St. Symeon is more mystifying, given that St. Nikodemos himself produced the first collected edition of his works.

Very little is known for sure about the origin of Philokalia and how the texts were selected. It belongs to a reform movement that sought to return to original monastic traditions of Athonite monks known as the “Kollyvades.” However, in 1793, very shortly after the publication of the Philokalia, a Slavonic translation, called the Dobrotolyubie (a calque of philokalia), by the Ukrainian monk, St. Paisy Velichkovsky, was published in Ia§i in Moldavia (modern Romania). St. Paisy’s selection is smaller than the Greek version (and, in particular, omits the more intellectually demanding writers such as Maximos the Confessor and even Gregory Palamas), but draws on the same collection of material. His translation, which took some years, cannot be a selection from the printed Greek text, and must therefore be thought of as drawing from an already known – and presumably traditional – collection of ascet- ical texts, already current on the Holy Mountain. In 1822 a second edition of the Dobrotolyubie came out, supplemented by various other texts from the Greek Philokalia. Between 1877 and 1905 there appeared in Russia a further translation in five volumes, translated (into Russian) by St. Theophan the Recluse. This version restores Maximos and Palamas, omitted by St. Paisy, and considerably expands the list of philokalic fathers, including John of Sinai (in extracts), as well as the ascetics of Gaza, Barsanuphios, John, and Dorotheos, and St. Isaac the Syrian (in his lifetime a Nestorian bishop), as well as a more substantial group of texts by St. Symeon the New Theologian, and further texts from the original Greek Philokalia.

The immediate influence of the Philokalia, or rather Dobrotlyubie, was most immediately felt in Russia, where it was read by St. Seraphim of Sarov and the monks of Optina Pustyn’, the monastery south of Moscow that became a center for the Slavophiles and other members of the Russian intelligentsia. It led to a revival of monasticism in Russia, in which stress was laid on the practice of private prayer, especially the Jesus Prayer, and the institution of spiritual fatherhood (starchestvo), echoes of which can be heard in Dostoevsky’s Brothers Karamazov. It also inspired a revival of interest in the fathers, among whom the philokalic fathers formed a core. A work with a complex history, known in English as The Way of the Pilgrim, popularized the Jesus Prayer and (in its most common form) the institution of starchestvo, both in Russia and then through translations in the 20th century throughout the world. The Jesus Prayer, from being the preserve of primarily Athonite monks, came to gain a popularity that now reaches well beyond the bounds of Orthodoxy.

in the 20th century there were translations into many European languages, mostly selections from the Greek Philokalia. in the English-speaking world the first translations were from the Russian of St. Theophan’s Dobrotolyubie, though there is a projected (not yet completed) translation of the whole Greek text of the original. Rather different is the Romanian translation, the work of the great Romanian theologian, Fr. Dumitru Staniloae. This version is much longer than the Greek original, and often includes a more comprehensive selection of the works of the fathers included, as well as supplementing the selection found in the Greek version by other philokalic fathers, frequently following the example of St. Theophan. it also includes a commentary, recognizing that a reader of a printed book now cannot be sure of the guidance of a spiritual father, a thing taken for granted by the original compilers.

SEE ALSO: Elder (Starets); Hesychasm; Jesus Prayer; Pilgrim, Way of the; St. Gregory Palamas (1296–1359); St. Isaac the Syrian (7th c.); St. Maximos the Confessor (580–662); St. Nikodemos the Hagiorite (1749–1809); St. Paisy Velichovsky (1722–1794); St. Seraphim of Sarov (1759–1833); St. Symeon the New Theologian (949–1022); St. Theophan (Govorov) the Recluse (1815–1894); Sts. Barsanuphius and John (6th c.); Staniloae, Dumitru (1903–1993)

REFERENCES AND SUGGESTED READINGS

Kadloubovsky, E. and Palmer, G. E. H. (1973) Writings from the Philokalia on Prayer of the Heart. London: Faber and Faber.

Palmer, G. E. H., Sherrard, P., and Ware, K. (1979) The Philokalia, Vols. 1– 4. London: Faber and Faber. Smith, A. (2006) The Philokalia: The Eastern Christian Spiritual Texts – Selections Annotated and Explained. Woodstock, VT: Skylight Paths.