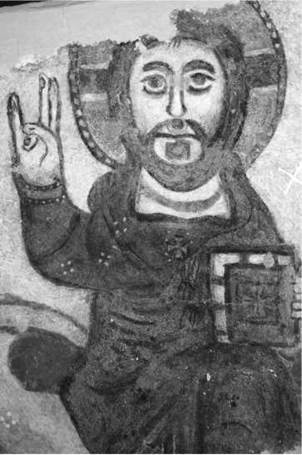

Pantocrator Icon

MARIA GWYN MCDOWELL

The broad range of Pantocrator (“Ruler” or “Preserver of all”) icons of the Lord in majestic judgment and blessing serve as “a flexible spiritual aid for the devout viewer” (Onasch and Schnieper 1995: 129). Initially appearing on coins and in manuscripts, then domes and apses, Pantocrator icons proliferated during the high Middle Ages. A bearded Christ, hair neatly parted, sits on a throne (often absent), right hand raised in blessing, left hand holding the gospel, expression varying from severe to compassionate. The background may include a mandorla, angelic figures, and gospel symbols. Famous examples include the earliest known 6th-century Sinai encaustic and the 11th-century Daphni mosaic.

SEE ALSO: Deisis; Icons

REFERENCES AND SUGGESTED READINGS

Onasch, K. and Schnieper, A. (1995) Icons: Fascination and Reality. New York: Riverside Books.

Ouspensky, L. and Lossky, V. (1982) The Meaning of Icons. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

Plate 48 Coptic fresco of Christ in glory from the Monastery of St. Antony by the Red Sea. Photo by John McGuckin.

Papacy

AUGUSTINE CASIDAY

A statement of the Eastern Orthodox ideal of the papal office, and its role in relation to the churches, can be supplied from St. Ignatius of Antioch’s salutation in his letter To the Romans, where he speaks of how the pope presides over the Church of Rome: “which presides in love.” Similarly, the problems experienced by Orthodox Christians with respect to the papacy can also be summed up from Ignatius’ further description of the Church of Rome as functioning to “maintain the law of Christ.” Under the concept of “maintaining the law of Christ” can be accommodated many of the Eastern Christian world’s experiences of the papacy that have been disagreeable, ranging from doctrinal assertions to political interventions, with the result that Orthodox perspectives on the papacy and especially its ecclesiological theory of primacy, above all in the second millennium of Christianity, have frequently been negative. Attention to several key episodes and particular claims will substantiate and nuance this general view.

Ignatius’ high regard was reinforced by Rome’s ancient reputation for orthodoxy, unrivalled by any other major see in the early Christian world. Situated a convenient distance from an interfering emperor, the pope of Rome almost always spoke conservatively for the good of the churches, and with a degree of impartiality, even if that came occasionally at a steep price. During the 7th-century Monothelite controversy, Pope Martin I paid with his life for opposing imperial policy. During the same crisis, St. Maximos the Confessor exclaimed at his trial: “I love the Romans because we share the same faith, whereas I love the Greeks because we share the same language.” But already by Maximos’ day a far-reaching difference between Greek and Latin theology was emerging as a contested issue, namely, the broad-based western affirmation that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father “and from the Son” or, in Latin, filioque (Louth 2007: 84–6). Initially outside of Rome, and eventually in Rome itself, that clause was incorporated into the Nicene- Constantinopolitan Creed. Such a modification raised important questions about what kind of authority the pope claimed to alter the creed set out by an ecumenical council. It also created a symbolic issue of high theological significance over which Orthodox and Latin Christians would argue fiercely.

With the increasing social and political prominence of the Roman Church in postByzantine Italy, the parameters of papal leadership expanded and frequently clashed against the secular powers of the Franks, the Byzantines, the Lombards, and others (see Noble 1984). Religious clashes occurred, as we have noted, increasingly over the matter of the filioque. Was the pope’s authority limited to final jurisdiction for appeals (as was the general eastern opinion in the first millennium) or did he enjoy the prerogative to intervene spontaneously whenever and wherever he considered such intervention justified (as became an increasingly affirmed Latin theory based on the idea of the pope as the extraordinary vicar of St. Peter)? What of the matter of jurisdictions extending as a result of sometimes competitive missionary activity (see Louth 2007: 167–92)? It was by no means unheard of for papal power to be exercised against the interests of the Christian East. Conflicting interests naturally led to confrontations, such as can be seen in Pope Nicholas I’s interventions during the patriarchate of Photios (Chadwick 2003: 95–192). Nicholas eventually answered an appeal by Photios’ deposed predecessor, but surely was also interested in the Christianization of Bulgaria, poised to come under either Roman or Constantinopolitan influence. For decades after this period, problems were rife between the Constantinopolitan patriarchate and the papacy, and matters only worsened as time went on. As Chadwick describes it: “In the century following the patriarchate of Photios, relations between Constantinople and Rome or the West generally fluctuated in close correspondence with political factors, and political concerns became a more potent factor than religious or theological matters” (2003: 193).

In 1054 another rupture opened in the tense existing communion between Rome and Constantinople, caused by diverging practices in liturgy and church discipline, and exacerbated by irreconcilable expectations about the exercise of authority in such cases (Chadwick 2003: 206–18; Louth 2007: 305–18). Although the mutual excommunications delivered in July 1054 were of doubtful importance, or even legality, in retrospect they more and more came to signify the formal separation ofthe Western Catholic Church from the Eastern Orthodox Churches. The events of 1054 certainly reveal “underlying issues of authority that were not to go away” (Louth 2007: 318).

That a confluence of competing political, doctrinal, and canonical interests contributed substantially to the estrangement of the Christian West from the Orthodox world is by no means solely a modern perception. The 12th-century historian Anna Comnena bundled ecclesiastical privileges together with political ascendancy in her claim for Constantinopolitan primacy: “The truth is that when power was transferred from Rome to our country and the Queen of Cities, not to mention the senate and the whole administration, the senior ranking archbishopric was also transferred here” (Alexiad 1.13). Her assessment suggests that 11th-century Rome was commonly seen by the Byzantines to lack ecclesiastical and political preeminence; and its claims for primacy as refuted in a reading of the Chalcedonian canons about jurisdictional precedence that interpreted Rome as having been subordinated to Constantinople. Such is Anna’s brisk response to the Gregorian reforms of an ascendant papacy.

Relations between the sees of Rome and Constantinople continued to deteriorate during the course of the Crusades. Anna Comnena saw in them, from their inception, a sinister western plot to subvert Constantinople (Alexiad 10.5), an eventuality which indeed transpired in 1204. As the figurehead for the Christian West, the papacy’s reputation in the East was enormously damaged by the fall of Constantinople to Latin Crusaders, and by the papacy’s subsequent activities, installing parallel Latin patriarchates in the conquered territories.

The popes hosted several attempts at reconciliation between the churches, such as the Second Council of Lyons (1274) and the Council of Ferrara-Florence (1438–9). Sometimes the initiative in reconciliation came from the East, as with the Union of Brest (1596), or it may have been a personal initiative, such as the contributions by Leo Allatius (1648) or Vladimir Solovyov. But these attempts were all overshadowed by widespread Orthodox distaste for the “Unia,” or Eastern-Rite Christian churches that accepted Papal obedience. The papacy’s invitation to the leading Orthodox hierarchs to attend Vatican Council I in the mid-19th century drew from them only a formal rebuke of his jurisdictional pretensions. Much tension still exists in terms of the papacy’s installation and continuing administration of a parallel Latin hierarchy in Orthodox lands (such as Russia).

In recent times, however, some Orthodox theologians have been revisiting the question of the papacy in a more pacific light (see Meyendorff 1992). The mutual excommunications of 1054 were rescinded on December 7, 1965 in a dramatic mutual gesture of reconciliation between Pope Paul VI and Patriarch Athenagoras of Constantinople (Abbot and Gallagher 1966: 725–7); and subsequent Constantinopolitan patriarchs have continued what has been called the “Dialogue of Love.” It suggests that further developments of Orthodox reflection on the role and position of the papacy will be forthcoming.

SEE ALSO: Church (Orthodox Ecclesiology); Eastern Catholic Churches; Episcopacy; Filioque; Rome, Ancient Patriarchate of; St. Maximos the Confessor (580–662); St. Photios the Great (ca. 810–893); Sts. Constantine (Cyril) (ca. 826–869) and Methodios (815–885); Solovyov, Vladimir (1853–1900)

REFERENCES AND SUGGESTED READINGS

Abbot, W. and Gallagher, J. (ed. and trans.) (1966) The Documents of Vatican II. New York: Corpus Press.

Allatius, L. (1648) De ecclesiae occidentalis atque orientalis perpetua consensione. Cologne:

Kalcovius.

Allen, P. and Neil, B. (ed. and trans.) (2004) Maximus the Confessor and His Companions: Documents from Exile. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chadwick, H. (2003) East and West: The Making of a Rift in the Church. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Comnena, A. (1969) The Alexiad, trans. E. R. A. Sewter. London: Penguin.

Louth, A. (2007) Greek East and Latin West: The Church ad 681–1071. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

Meyendorff, J. (ed.) (1992) The Primacy of Peter, 2nd edn. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

Noble, T. (1984) The Republic of St. Peter: The Birth of the Papal States, 680–825. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.