Africa, Orthodoxy in

JUSTIN M. LASSER

Christianity on the African continent begins its story, primarily, in four separate locales: Alexandrine and Coptic Egypt, the North African region surrounding the city of Carthage, Nubia, and the steppes of Ethiopia. The present synopsis will primarily address the trajectories of the North African Church, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, and the Nubian Orthodox Church. The affairs of Christian Alexandria and the Coptic regions have their own treatments elsewhere in the encyclopedia.

ROMAN-COLONIAL NORTH AFRICA

After the Romans sacked the city of Carthage in 146 during the Third Punic War, they began a sustained colonizing campaign that slowly transformed the region (modern Tunisia and Libya) into a partially “Romanized” society. In most instances, however, the cultural transformations were superficial, affecting predominantly the trade languages and local power structures. It was Julius Caesar who laid the plans for Carthage’s reemergence as Colonia

Junonia in 44 bce. This strong colonial apparatus made North African Christians especially susceptible to persecution by the Roman authorities on the Italian Peninsula. Because the economic power of Carthage was an essential ingredient in the support of the citizens in the city of Rome, the Romans paid careful attention to the region. The earliest extant North African Christian text, the Passion of the Scillitan Martyrs (180 ce), reflects a particularly negative estimation of the Roman authorities. Saturninus, the Roman proconsul, made this appeal to the African Christians: “You can win the indulgence of our ruler the Emperor, if you return to a sensible mind.” The Holy Martyr Speratus responded by declaring: “The empire of this world I know not; but rather I serve that God, whom no one has seen, nor with these eyes can see. I have committed no theft; but if I have bought anything I pay the tax; because I know my Lord, the King of kings and Emperor of all nations.” This declaration was a manifestation of what the Roman authorities feared most about the Christians – their proclamation of a “rival” emperor, Jesus Christ, King of kings. The Holy Martyr Donata expressed that sentiment most clearly: “Honor to Caesar as Caesar: but fear to God.” Within the Roman imperial fold such declarations were not merely interpreted as “religious” expressions, but political challenges. As a result the Roman authorities executed the Scillitan Christians, the proto-martyrs of Africa. Other such persecutions formed the character and psyche of North African Christianity. It became and remained a “persecuted” church in mentality, even after the empire was converted to Christianity.

By far the most important theologian of Latin North Africa was Augustine of Hippo (354–430). His profound theological works established the foundations of later Latin theology and remain today as some of the most important expressions of western literary culture. His articulation of Christian doctrine represents the pinnacle of Latin Christian ingenuity and depth (see especially, On Christian Doctrine, On the Holy Trinity, and City of God). It also should be noted that Augustine, to a certain degree, “invented” the modern genre of the autobiography in his masterful work, the Confessions. However, Augustine drew on a long-established tradition of Latin theology before him as expressed in the writings of Tertullian, Minucius Felix, Optatus of Milevis, Arnobius, and Lactantius, among others, in the period of the 2nd through the 4th centuries.

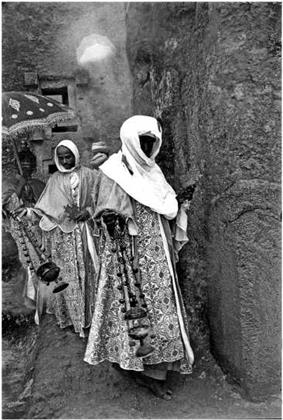

Plate 1 Ethiopian

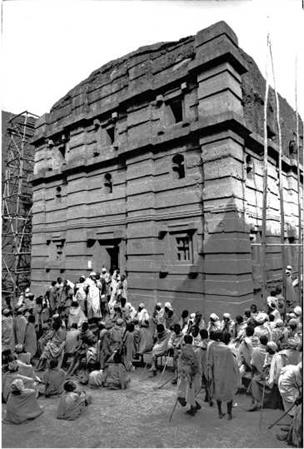

Plate 2 Pilgrims gathered around the Ethiopian Orthodox Church of Holy Emmanuel. Photo Sulaiman Ellison

TERTULLIAN

Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus’ (ca. 160–225) masterful rhetorical skill manifests the sentiments of the North African population in regard to the Roman authorities and various “heretical” groups. His terse rhetoric also represents the flowering of Latin rhetorical dexterity. Tertullian created many of the most memorable proclamations and formulae of early Christianity, several of which characterize his negative estimation of philosophical “innovators” – “What has Athens to do with Jerusalem?” he asked, casting aspersions on the utility of philosophy in the formulation of church teachings. His heresiological works laid the groundwork for many of the Orthodox responses to the Gnostics, Monarchians, and Marcionites, among others (The Apology, Against Marcion, Against Praxeas, Against Hermogenes). Tertullian also provided the Latin Church with much of its technical theological vocabulary (terms such as “person,” “nature,” and “sacrament”).

LACTANTIUS

Lactantius (ca. 250–325) differs from Tertullian in a variety of ways, but none is as clear as his different style of writing. Lactantius, to a certain degree, represents the first Christian “systematic” theology. This genre was markedly different from the apologetic treatises which were more common in the 2nd century. His is a highly eschatological vision, but allied with a deep sense that Christianity has the destiny to emerge as the new system for Rome, and his thought is colored by his legal training. He manifests a unique window into ancient patterns of pre-Nicene western Christian thought in philosophical circles around the Emperor Constantine. However, as we shall see, the contributions of North African Christianity cannot simply be limited to the intelligentsia and the cities. Much of its unique Christian expression was manifested outside Carthage.

CYPRIAN OF CARTHAGE

The great rhetorician Cyprian of Carthage (ca. 200–58) represents the Orthodox response to the crises in the North African Church resulting from the Roman persecutions. He was a leading Romano-African rhetorician, and became a convert to the Christian faith under the tutelage of Bishop Caecilius, a noted “resister.” Cyprian found himself at the center of the competing positions in the face of Roman persecution. In 250 the Emperor Decius demanded that all citizens should offer sacrifices to the Roman gods. Cyprian, in response, chose to flee the city and take refuge. There were many Christians in Carthage who looked upon this flight with great

disdain. While Cyprian was in hiding, many of his faithful confessed their faith and died as martyrs, while others elected to offer sacrifices to the gods. These circumstances led to the controversy over whether or not lapsed Christians should be readmitted into the church. With the potential onslaught of new persecutions, Cyprian advocated reconciliation. This crisis produced some of the most profound expositions of Christian ecclesiology (see especially, Unity of the Catholic Church and On the Lapsed). In 258 Cyprian was martyred under Galerius Maximus during the reign of Emperor Valerian. His writings have had a deep effect on the ecclesiological thought of the Eastern Orthodox world, though in many instances they have been superseded, for the West, by the ecclesiological writings Augustine would produce after his encounter with the Donatists. Cyprian’s theology and noble leadership bear witness to the fact that the Donatist controversy was not a disagreement between enemies, but brothers

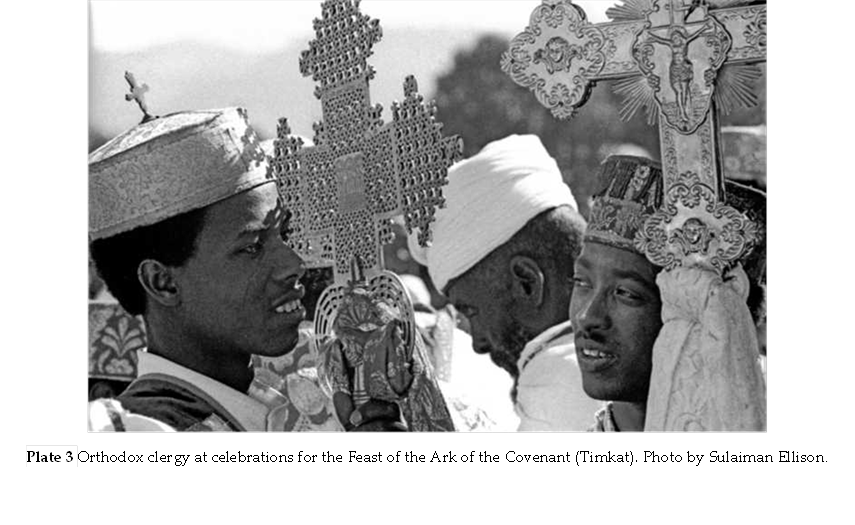

Plate 3 Orthodox clergy at celebrations for the Feast of the Ark of the Covenant (Timkat). Photo by Sulaiman Ellison.

AUGUSTINE AND THE DONATISTS

The history of the church in the shadow of the great trade city of Carthage and the hill country of Numidia is greatly obscured by ancient rhetorical devices and the rhetoric of privilege in the classical Roman social structure. As much as the history of Christian Numidia has been characterized by the Donatist schism, it is more a story of the clash between village and city, or colonized and colonizer. It would be easy to approach African Christianity through the rhetorical prism of the capital cities alone, but that would be less than half the story. Indeed, the Christianity of Carthage was very different from the Christianity in the hill country and villages of Numidia. In classical definition (largely the manner in which St. Augustine classified them, his major opponents), the Donatists were a schismatical group that insisted on absolute purity of the clergy and the Orthodox communion. They became emboldened by their perseverance during persecution and demanded the same of every Christian. They also expressed a remarkable literalness in exegetical interpretation and renounced those who turned over the sacred Scriptures to the authorities as traditores (traitors). Traditionally, they also expressed a strange eagerness for the “second baptism” of martyrdom. The memory of the Numidian Donatists has been greatly overshadowed by Augustine of Hippo’s writings and his international reputation. Augustine successfully characterized the Donatists as “elitists,” but this has partly occluded the more correct view of the movement as chiefly a village phenomenon, closer, perhaps, to the poorer life of the countryside than that known by Augustine, who clearly lived far more happily in the Roman colonial establishment. Augustine’s friend Alypius described the Numidian Donatists thus: “All these men are bishops of estates [fundi] and manors [villae] not towns [civitates]” (GestaColl. Carthage I.164, quoted in Frend 1952: 49). The charge of sectarian elitism was a means to delegitimize the rural bishops, as the city bishops assumed that the ecclesiastical hierarchy should reflect the Roman imperial hierarchy, and they considered the Donatist flocks too small to have a significant say. In the Roman world, power was centralized in the cities, not in the manors. The estates (fundi) existed only as a means of supplying the cities, not as autonomous entities in themselves. The Numidian Christians challenged this social structure with the ethical tenets expressed in the teachings of Christ against wealth.

Catholic Christians in North Africa were primarily Latin and Punic speaking peoples. Many of the Donatists were primarily speakers of the various Berber languages, which still exist today in North Africa (Frend 1952: 52). The segregation of the Catholic-Donatist controversy along these ethnic lines may demonstrate that theology was not necessarily the primary reason for the schism. In fact the Numidian Donatists represent the first sustained counter-imperial operation within Christian history. It was in many instances a rural movement against the colonial cities and outposts of the Romans in the north. The schism, nevertheless, undoubtedly weakened North African Christianity in the years before the advent of the “barbarian” invasions, followed by the ascent of Islam: events which more or less wholly suppressed Christianity in the Northern Mediterranean littoral. Augustine’s theology of church unity stressed wider international aspects of communion (catholic interaction of churches) and was highly influential on later Latin ecclesiological structures. He also elevated high in his thought the conception of caritas (brotherly love) as one of the most important of all theological virtues.

The many internal disagreements in the North African Church and the success of the Donatist martyrs led to an increased isolation of the region. The gradual collapse of Roman authority is reflected in Augustine’s City of God. Soon after he wrote the work, the king of the Vandals, Gaiseric, sacked Carthage and the wider region in 439. The loss of North Africa sent shock waves through the Christian world. Emperor Justinian led one final attempt at reannexing North Africa in 534, and actually succeeded for a period of time. However, the continuing internal divisions, the economic deterioration, and the failing colonial apparatus, all made it difficult to keep the region within the Romano- Byzantine fold. The last flickers of North African theological expression were witnessed by Sts. Fulgentius of Ruspe, Facundus of Hermiane, and Vigilius of Thapsus. In 698 Carthage was sacked by the invading Islamic armies, sealing the fate of the North African Christians and ending their once colorful history.

ETHIOPIA

The beginnings of the church in Ethiopia are difficult to decipher given the ancient confusion over the location of Ethiopia. In ancient texts India was often confused with Ethiopia and vice versa. In classical parlance “India” and “Ethiopia” merely suggest a foreign land sitting at the edge of the world, existing as the last bastion of civilization before the “tumultuous chaos of the barbarians.” Their great distance away from Greece was also meant to convey a world of innocence and wonder: a “magic land.” This hardly tells us much about the actual life of the Ethiopians in Africa. The very term Ethiopia derives from a hegemonic Greek racial slur delineating the land of “the burnt-faces” or “fire-faces.” But a closer look reveals something very different, for the cultural achievements of the peoples of the Ethiopian highlands (in ancient times more of the coastal hinterland was under Ethiopian control than later on after the rise of Islam) are both astounding and utterly beautiful. A visit to the rock-hewn churches of Lalibela or an encounter with the haunting chants of the Christians at prayer is quite unforgettable. Ethiopia presents itself to the visitor as another “land of milk and honey,” a second Eden indeed, since the hills of Ethiopia, along with Kenya, were the first places that humans ever walked on the face of the earth. Modern Ethiopia and Eritrea are composed of a very diverse group of people. The same doubtless could be said of ancient Ethiopia.

The history of the church here is difficult to tell in a chronological order, so many have been the devastations and loss of records that there are large holes in the evidence, and much legend replaces them. Most scholars investigating the origins of Ethiopian civilization begin their stories with the South Arabian immigrants that began to settle in the coastal city of Adulis on the Red Sea and the northern city of Aksum (Axum) in search of trade in the 5th century BCE. While it is true that South Arabian settlers partly altered some of the indigenous racial elements of the Ethiopian lands, a focus on colonial influences as explaining the distinct Ethiopic-African characteristics masks the fact that Ethiopian civilization was already far older and much more established than anything these colonial visitors brought. Christianity, however, probably came in with trade movements, as it did elsewhere. The majority of the Ethiopian populace have been categorized by a common root language called “Kushitic.” This language is perhaps related to the biblical people mentioned in Genesis as the Kushites. Ancient Kushite elements are still exhibited in the unique architecture of the earliest Orthodox churches in the region and the healing and dancing ceremonies that still dominate the Ethiopian Orthodox experience; though the greatest contribution was the eclectic and rhythmic language known as Ge’ez (Ethiopic). Indeed, the best place to begin a history of the Ethiopian and Kushitic peoples is the analysis of their poetic language. Ge’ez exhibits South Semitic roots related to the Sabaic language as well as Kushitic roots. Biblically speaking, then, Ethiopia was the land of Kush, and the story concerning the emergence of the Orthodox Church in Ethiopia is really the continuing story of the cultural eclecticism in the North of Ethiopia (the mixing of Southern Arab and native African peoples) and in the South, the negotiation of differing spiritual perspectives with a peculiar form of Judaism; relations between Ethiopia and Jerusalem comprising one of the most ancient routes known to the Africans by sea and land. Church history in this case is also a story of an imperial campaign to unite the South with the North and its newly adopted religion of Christianity, a movement that entailed the destruction of indigenous religions in the environs of the kingdom of Aksum.

This strong element of synthesis is what unifies the Ethiopian peoples. The earliest suggestion of a kingdom in the land of Kush derives from the Azbi-Dera inscription on a large altar dedicated to the god Almouqah, which was a South Arabian deity. As the South Arabian traders moved into the interior of the Ethiopian highlands, they brought with them a lucrative trade market. It seems the first group to profit from this trade was the city of Aksum in the North. Earlier Eurocentric scholars working from unexamined racist premises viewed the expansion of Aksum as a Semitic victory of the forces of “civilization” in Ethiopia, as if the indigenous groups were not civilized at all before this. The historical and cultural record simply does not support such a reconstruction. The Ethiopian highland was already home to a diverse array of indigenous cultures, but little is known about them as archeological work has barely been initiated in the region outside of Aksum and other Christian holy sites. The kingdom of Aksum, however, is the first cultural group to succeed in edging its way into considerable power and cultural influence. This was made possible by the apparent conquest of the neighboring kingdom of Meroe in the 4th century BCE. The earliest mention of the kingdom of Aksum was in the 2nd century CE by Ptolemy. An anonymous text called the Periplos is the first to describe the boundaries of the Aksumite territories, which are closely related to the modern state of Eritrea along the coast, extending into Northern Ethiopia.

Beyond the historic-archeological record, the Ethiopian Orthodox faithful have a variety of “foundation stories” of their own. The best known is the story of the Ethiopian eunuch in the Acts of the Apostles (8.26–40). On this occasion an Ethiopian eunuch serving in the royal court of the queen (the Candace) of Ethiopia (which St. Luke mistakes for a personal name) was baptized by the Apostle Philip and sent on a mission to preach the gospel in Ethiopia. This tells us, at least, that the presence of Ethiopian “Godfearers” in Jerusalem was already an established fact in the time of Jesus. The most historically substantial foundation story is that of the Syrian brothers Frumentius and Aedesius in the 4th century. There may well have been various forms of Christianity present in Ethiopia before Frumentius and Aedesius, but they were the first to convert a royal Ethiopian court to the new faith. This seems to have been a common missionary strategy of the church at this time: convert the royal courts and the countryside would follow. This strategy had the advantage of rapidity, but often failed to establish indigenous forms of Christianity that could survive future religious sways of the royal courts themselves. The defect of this strategy is exemplified in the rapid demise of the Nubian Orthodox Church, to the south, after eleven hundred years, when the royal court went over to Islam.

According to the histories, Frumentius and Aedesius arrived because of a shipwreck and were strangely asked by the recently widowed queen of Aksum to govern the kingdom until her young son was experienced enough to rule the kingdom himself. Once the young Ezana became king, the Syrian brothers left the kingdom. Aedesius returned to Tyre and Frumentius traveled to Alexandria where the great Bishop Athanasius insisted on appointing him as the first bishop of Ethiopia, and sent him back to minister to the court. This story contains much historically viable material (Syrian traders who are co-opted as state councilors) but is colored with numerous legendary flourishes. The story about Frumentius and Athanasius may well indicate more evidence of the very active campaign by St. Athanasius to establish a politically important support center for his struggle against Arianism in the Roman Empire to the far north. This is substantiated by a letter of Emperor Constantius to King Ezana and Shaizana. In this letter Constantius informed them that Frumentius was an illegitimate bishop, as he had been consecrated by the “unorthodox” incumbent, St. Athanasius, and that Frumentius should return to Alexandria to be consecrated under the “orthodox” (Arian) bishop, George of Cappadocia (Kaplan 1984: 15).

The conversion of the royal court at Aksum was of great interest to the Romans, since Ethiopia was of great strategic importance for the empire in the North. The lucrative trade from the Southern Arabian Peninsula and exotic luxuries from sub-Saharan Africa provided much incentive for the Romans to want to control the region. Additionally, the strategic location of Ethiopia ensured a more secure buffer for Egypt from the East, the bread basket of the empire. For the Aksumites, establishing the favor and support of the empire to the north established their kingdom as the main cultural and political force in the Ethiopian highlands. This was especially important for the Aksumites given their delicate political state in the time of Athanasius and Emperor Constantius. Even so, the sudden change in religious allegiance happening in the 4th-century royal court was hardly embraced by the population as a whole. Beyond the court, Christianity was scarcely in existence and lacked the appropriate catechetical structures to instill the Christian religion. The young King Ezana also struggled to balance the needs of his diverse kingdom with his newly adopted religion. In contemporary Greek inscriptions, which were obviously illegible to most of the indigenous peoples, Ezana referred to the Blessed Trinity and declared his status as a believer in Christ. However, in Ge’ez (Ethiopic) inscriptions he uses the vaguer term “Lord of Heaven” when addressing God (Kaplan 1984: 16). In this manner Ezana spoke to and for both the Christian and indigenous communities of his kingdom without offending either.

The consecration of Frumentius in Alexandria for the Ethiopian people established a hegemonic tradition of the ecclesiastical precedence of Alexandrian Egypt that afterwards dominated much of Ethiopian Orthodox history. This occasion was seen as the paradigm for all future consecrations of the Ethiopian hierarchs, and this state of affairs lasted until 1959. Too often, the senior Ethiopian hierarch who was nominated was not even Ethiopian. In the time of the Islamic domination of Egypt, these foreign bishops were often compromised by their Muslim overlords and by the interests of local politics in Alexandria, and sometimes adopted policies that were not always in the primary interests of the Ethiopian peoples. Sometimes the appointment of Alexandrian Coptic clergy was meant as a way of getting rid of troublesome rivals or delinquent clerics from the Egyptian Church (Kaplan 1984: 29–31). This paradigm also led to a consistent shortage of priests and bishops in Ethiopia. When a senior bishop died, there were often inter-regnum lapses of several years. After the time of Frumentius the Ethiopian Orthodox Church developed slowly, due to the strength of the indigenous faiths and the considerable lack of catechetical, clerical, and literary resources. After the Council of Chalcedon in 451, however, the strategic importance of Ethiopia emerged once again as far as the empire was concerned. As Constantinople lost control over Syria and Egypt, the condition of Ethiopian Orthodoxy became much more significant. The great pro- and anti- Chalcedonian conflicts of Alexandria were reflected in the Ethiopian highlands. Ethiopia became a battle ground for which party would win the ascendancy. The Monophysite clergy of Alexandria initiated dynamic missionary programs, focused on the winning of the Ethiopian people to the anti-Chalcedonian Coptic cause. To their efforts, already aided by the existing institutional links with Cairo and Alexandria, was added the influx of Monophysite missionaries displaced from Syria, Cappadocia, Cilicia, and other regions. This new impetus to evangelize Ethiopia arrived in the form of the Nine Saints (known as the Tsedakan or “righteous ones”) who remain of high importance in the later church history of Ethiopia. The nine saints (Abba Za-Mika’el (or Abba Aregawi), Abba Pantelewon, Abba Gerima (or Yeshaq), Abba Aftse, Abba Guba, Abba Alef, Abba Yem’ata, Abba Libanos, and Abba Sehma) established numerous monasteries in the Tigre region as well as the areas outside Aksum, working mainly in the northern regions of Ethiopia. The most famous of these monasteries is certainly that of Dabra Damo, which still thrives today. The most celebrated of the Nine Saints is Abba

Za-Mika’el, who composed an important Ethiopian monastic rule. Abba Libanos is credited with establishing the great monastic center of Dabra Libanos. The importance and influence of these two groups cannot be overstated. They are responsible for the formation of the Ethiopian biblical canon, the translation of many Christian texts from Greek and Syriac into Ge’ez, and establishing a strong monastic base which would stand the test of time.

During the reigns of King Kaleb and his son Gabra Masqal in the 6th century, the monastic communities were generously supported and the territories of the Christian kingdom expanded. However, much of this progress was greatly inhibited by the advent of Islam on the Arabian Peninsula. The extended period between the 8th and 12th centuries lends the scholar very few sources for Christian Ethiopia beyond the Coptic History of the Patriarchs (Kaplan 1984: 18). However, an estimate of conditions is certainly indicated by the fact that the Ethiopians operated without an archbishop for over a half a century at on point (Budge 1928: 233–4).

After the crisis of the Council of Chalcedon in 451 the Ethiopians, who recognized no ecumenical validity to conciliar meetings in the Byzantine world after Ephesus in 431, were more and more isolated from the wider Christian world, but with the advent of Islam and the many subsequent incursions into their territory, constantly eroding their hold on the littoral lands, the Ethiopians soon found themselves isolated from the entire Christian world, save for the occasional communications with the Coptic Orthodox in the distant North, by means of the difficult land and river route. Although this isolation proved problematic in some ways, in others it served to provide the space necessary for Ethiopia to develop and create its unique expression of Orthodoxy.

Towards the end of the 11th century the Aksumite Empire declined rapidly, which led to a gradual relocation of the central authorities into the central plateau (Tamrat 1972: 53–4). The Agaw people already populated this region and the Aksumite descendants started a concentrated campaign to Christianize the area. The Agaw leaders soon embraced Christianity and were integrated into the royal court so intimately that they eventually established their own successful dynasty known as the Zagwe, which ruled Ethiopia from 1137 to 1270. However, the Zagwe suffered from their apparent lack of legitimacy. Earlier Aksumite rulers had established the tradition of “Solomonic” descent in the legendary Kebra Negast (Glory of the Kings). The Zagwee were considered illegitimate by the Tigree and Amhara peoples in the North. The Zagwe dynasty is responsible for that jewel of Ethiopian church architecture, the city of Lali Bela. This incredible conglomeration of rock-hewn churches was meant to reproduce the sites of the holy land and established, for the Zagwe, a rival pilgrimage site opposed to Aksum in the North.

The Zagwee, however, were never able to unify the Ethiopian peoples under their banner. This inability to secure a wider consensus regarding their legitimacy as a royal line, despite the incredible accomplishments of the dynasty, fractured Christian Ethiopia; a fracture that still exists today in the painful animosities between the Tigrean people in Eritrea and the peoples of Ethiopia. In the late 12th and mid-13th centuries the expansion of Muslim trading posts channeling trade from the African interior to the wealthy Arabian Peninsula greatly strengthened the Amhara Ethiopian leaders who initiated this trade route (Kaplan 1984: 21). In time the weakened Zagwee dynasty gave way to the ambitious Amharic King Yekunno Amlak. However, during this period of rapid Islamic expansion, the Ethiopian rulers continued to splinter and struggle with problems of the succession. This inherent weakness later threatened the very continued existence of the Ethiopian “state»

It was with Yekunno Amlak’s son, King Amda Seyon, that the fortunes of the Ethiopian state turned. Amda Seyon was a shrewd military genius. He turned the tide of internal Ethiopian divisions by creating a centralized military force. Rather than depending on the countryside for local militia, he decided to unite mercenaries and local conscripts under commanders loyal to the royal court (Kaplan 1984: 22–3). In doing this he undercut the power of the local warlords. After subduing the resistant chieftains in the Aksumite and Tigre regions there was little further challenge to Amda Seyon’s legitimacy as an Amhara usurper. Having crushed his antagonists, he claimed the Solomonic line for himself. It was at this stage (14th century) that the great founding myth in the Kebra Negast became so central to Ethiopian Orthodox consciousness generally. It was first advanced by the rival Tigrean ruler Ya’ebika Egzi’, but was soon shrewdly co-opted by Amda Seyon. Prior to his rule the Ethiopian provinces were subjected to constant Islamic incursions. Aware of their isolated status, they followed a policy of appeasement. Under Amda Seyon the Ethiopians, with a more centralized military force, were now able to pursue a policy of aggressive reconquest, and actually succeeded in forcing certain Islamic regions into becoming vassal states. Additionally, the conquest and control of the lucrative trade route between the Arabian South and the African interior brought immense wealth to the new dynasty, which helped to solidify its political position.

The success and expansion of the medieval Ethiopian state was not without severe negative consequences. The church had become so inalienably married to the state by this time that the Christian mission began to include the subjugation of alien peoples. The Kebra Negast established a link between the line of King Solomon and the Ethiopian kings which granted them divine favor and a perceived duty to Christianize the region through force, if necessary. The Feteha Negast instructed the kings in the proper treatment of their pagan neighbors in terms redolent of the Qur’an. The Feteha Negast reads: “If they accept you and open their gates the men who are there shall become your subjects and shall give you tributes. But if they refuse the term of peace and after the battle fight against you, go forward to assault and oppress them since the Lord your God will give them to you.”

In this emerging colonial expansion of the Ethiopian state a form of feudalism was imposed on the conquered peoples. Churches were often guarded by the military, a fact that exposes something of the unpopularity of the church’s mission in the newly conquered tribal areas. The attempted Christianization of the Oromo peoples in the South, for example, brought with it rampant pillaging and extensive confiscation of lands. The Orthodox clergy and Ethiopian nobles were often given the confiscated lands to rule over as feudal lords, whereas the unfortunate Oromo were reduced to the plight of serfdom. This is a condition that Ethiopia never remedied and many ramifications from it still present themselves today as important human rights issues.

The feudal stage of Ethiopian history reached its pinnacle in the Gondar period between 1632 and 1855. During this period the country became deeply fragmented between the competing nobles, a condition that invited numerous incursions on the part of their Muslim neighbors. With the rise of Emperor Menelik II (ca. 1889) the country overthrew many of the feudal lords and moved toward a new and extensive form of political and social reunification. This was all halted during the reign of Emperor Haile Selassie I, when the Italian Army invaded and occupied Ethiopia in 1935. When the Italians left Ethiopia in 1941, Haile Selassie I was returned to power. However, the restored imperial period was not to last long. In 1974 a brutal communist regime took control of the country, inaugurating one of the most severe persecutions of Christians in Orthodox memory in those lands.

The Ethiopians have created and sustained one of the most unique expressions of world Christian Orthodoxy. One of the most intriguing aspects of the Ethiopian Church is its peculiar Jewish characteristics, the origins of which remain quite mysterious. The Ethiopian Orthodox still observe the Sabbath and continue to circumcise their male children as well as to baptize them. Moreover, they believe wholeheartedly that the original Ark of the Covenant was brought to their lands before the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple. Today, the Ark is believed to be housed in a small chapel in the city of Aksum and guarded by a lone hermit monk guardian who lives alongside it. Once a year an exact copy of the Ark is taken out of the chapel and venerated ecstatically by the faithful. The Ark plays such an important role within Ethiopian Orthodoxy that the Eucharist is celebrated over a miniature copy of the Ark (called a Tabot) in every Ethiopian church. The continued existence of Ethiopian and Eritrean Orthodoxy amid a sea of hostile neighbors is a testament to their zealous faith and deep roots.

Today, while having a separate patriarch, the Ethiopian Church continues with the closest of friendly relations with Coptic Alexandria. The Eritrean and Ethiopian faithful have moved apart following the divisive civil war of the late 20th century. Both Ethiopian families belong to the Oriental (Non-Chalcedonian) Orthodox family of churches, but rarely involve themselves in any form of international ecumenical discussions.

CHRISTIAN NUBIA

In 1960 the Islamic Egyptian authorities in the North flooded, as part of the Aswan project, many of the last vestiges of Nubian Christian antiquity. The construction of the Aswan dam devastated the archeological prospects of the region. Despite these trying circumstances there were many emergency archeological digs done at this time (mainly privileging Pharaonic remains) and some significant Nubian Christian artifacts emerged to give a slightly better shading to the obscure history of this once extensive sub-Saharan form of Orthodox Christianity. As with ancient Ethiopia, the exact geographical location of the Kingdom of Nubia is often obscured by geographical imprecisions in the ancient texts. Ibn Salim al-Aswani (975–96 CE), an important source for the later historian al- Maqrlzi, spent a significant amount of time among the Nubians and their royal court. To the Egyptians in the North, the Fourth Cataract along the Nile River marked the beginning of Nubian territory. The Egyptians to the north rarely ventured beyond the Fifth Cataract near the ancient city of Berber. The temperate climate to the south of the Fourth and Fifth Cataracts as well as less frequent Egyptian incursions allowed for the development of the African Kingdom of Meroe, on Meroe Island situated between the Atbara, Nile, and Blue Nile rivers. In this region dwelt the Kushites, Nubians, and Ethiopians. According to the Greek historian Strabo: “The parts on the left side of the course of the Nile are inhabited by Nubae, a large tribe, who, beginning at Meroe, extend as far as the bends of the river, and are not subject to the Aethiopians but are divided into several separate kingdoms” (Kirwan 1974: 46). The composition of what these separate kingdoms might be is very difficult to sort out historically and geographically. Generally, it seems the Nubian tribes settled between the Kingdom of Meroe in the South and Egypt in the North. The Nubians were perceived by their neighbors as “piratical” marauding tribes disrupting the trade between Egypt and the lucrative sub Saharan world represented by the Kingdoms of Meroe and Aksum.

A 5th-century Greek inscription of the Nubian King Silko describes his campaigns into Lower Nubia against the Blemmyes, another tribe regarded by the wider world (especially the Roman Empire) as “brigands.” After sacking a series of former Roman forts used by the Blemmyes, King Silko incorporated them into his kingdom and claimed the title of “King of the Nobades and of all the Ethiopians.” This campaign ensured the continued existence of the Nubian Kingdom for centuries to come. It would endure as a Christian reality until the 15th century. Because the Nubian Kingdom controlled the trade route between Roman Egypt and the sub-Saharan world in Late Antiquity, it also became a very important piece of the global puzzle within the later Byzantine and Islamic political strategies. Empress Theodora, Justinian’s wife, recognized the importance of the trade route and sent a series of Christian missions to the Nubian Kingdom. The success of these missions, as described by John of Ephesus, converted the Nubians to the non- Chalcedonian cause. As in Ethiopia, the Nubians were ecclesiastically related to the jurisdiction of the Coptic Egyptian authorities in the North, and the patriarch of Alexandria appointed their bishops. The vitality of this Christian tradition is evinced by their beautiful frescoes and ornate churches. Even with the decline of Christian civilization in the North, and with only the Nile as a tentative route of connection, the Christian Nubians persevered for centuries. Their increasing isolation from the rest of the Christian world made them more vulnerable to Islamic incursions in the 12th and 13th centuries. When the royal court at Dongola finally converted to Islam, the isolated condition of the Nubians, their ecclesial dependence on Egypt, and the manner in which the church had always been so heavily sustained by the power of the royal court created the climate for a rapid dissolution. In a relatively short time the Christian Nubian Kingdom faded away into nothing more than a memory, and a few alluring fragments of art history from the site at Faras (Vantini 1970).

Orthodox Christianity in Africa is an ancient and complex story: a confluence of many peoples, languages, and cultures. It was deeply rooted before ever the western colonial powers thought of mounting missions and has endured long after the colonial powers have themselves fallen.

SEE ALSO: Alexandria, Patriarchate of; Coptic Orthodoxy; Council of Chalcedon (451); Monophysitism (including Miaphysitism); St. Constantine the Emperor (ca. 271–337)

REFERENCES AND SUGGESTED READINGS

Brown, P. (2000) Augustine of Hippo:

A Biography, 2nd edn. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Budge, E. A. W. (1906) The Life and Miracles of Takla Haymanot. London: Methuen.

Budge, E. A. W. (1922) The Queen of Sheba and Her Only Son Menyelek. London: Methuen.

Budge, E. A. W. (1928a) The Book of the Saints of the Ethiopian Church. London: Methuen.

Budge, E. A. W. (1928b) A History of Ethiopia: Nubia and Abyssinia, 2 vols. London: Methuen Frend, W. H. C. (1952) The Donatist Church: A Movement of Protest in Roman North Africa. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Kaplan, S. (1984) The Monastic Holy Man and the Christianization of Early Solomonic Ethiopia. Frankfurt: Franz Steiner.

Kirwan, L. P. (1974) “Nubia and Nubian Origins,” Geographical Journal 140, 1: 43–51.

Leslau, W. (1945) “The Influence of Cushitic on the Semitic Languages of Ethiopia: A Problem of Substratum,” Word 1: 59–82.

Phillipson, D. W. (ed.) (1997) The Monuments of Aksum: An Illustrated Account. Addis Ababa: University of Addis Ababa Press.

Shinnie, P. L. (1978) “Christian Nubia,” in J. D. Fage (ed.) The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tamrat, T. (1972) Church and State in Ethiopia 1270–1527. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Vantini, J. (1970) The Excavations at Faras: A Contribution to the History of Christian Nubia. Bologna: Editrice Nigrizia.