Jesus Prayer

METROPOLITAN KALLISTOS OF DIOKLEIA

A short invocation, designed for frequent repetition, addressed to Christ and using his human name “Jesus” (Mt. 1.21). Most commonly the Jesus Prayer is said in the form “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me” (see the prayer of the blind man Bartimaeus in Mk. 10.47; Lk. 18.38). But there are many variants. Particularly in the Russian tradition, the words “the sinner” are often added as the end (see the prayer of the publican in Lk. 18.13). It is possible to say in the plural “have mercy on us.” The prayer may be abbreviated: “Lord Jesus, have mercy,” “My Jesus,” or even “Jesus” on its own (but this is rare in Orthodoxy, although frequent in the medieval West). What is constant among all the variants is the employment of the name “Jesus.” There are basically two ways in which the Jesus Prayer is said: either it is recited on its own, in conditions of outward quiet, as part of our appointed prayer time; or else it is used in a free way, in unoccupied moments as we go about our daily tasks (when performing simple manual labor, walking from place to place, and so on).

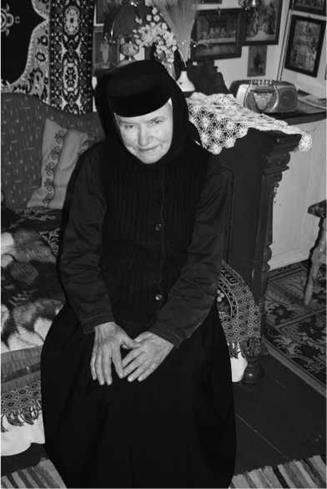

Plate 37 One of the nuns in the Varatec monastic community in Romania: a veritable monastic village of many buildings, and several thousand nuns. Photo by John McGuckin.

Fundamental to the tradition of the Jesus Prayer is a sense of profound reverence for the holy name “Jesus.” This is felt to act in a semi-sacramental way as a source of grace and strength. There is, it is believed, an integral connection between the name and the person named; to call on the Son of God by name is to render him directly and dynamically present. In this way the distant origin of the Jesus Prayer is to be found in the veneration of the name of God in the Old and New Testaments. Especially influential is Philippians 2.10: “At the name of Jesus every knee should bend” (cf. Jn. 16.23–24; Acts 4.10–12). The same reverence for the name is found in early Christian texts such as the 2nd-century Shepherd of Hermas: “The Name of the Son of God is great and boundless, and it upholds the whole world” (Similitudes 9.14.5).

The more immediate source of the Jesus Prayer is the practice of “monologic prayer” (i.e., prayer of a single word or phrase) found among the monks of 4th-century Egypt. Seeking to fulfill Paul’s injunction to “Pray without ceasing” (1Thes. 5.17), while performing manual labor they repeated short phrases or sentences, often from Scripture (e.g., Ps. 50/51.1). Augustine of Hippo (354–420) described these prayers as “suddenly shot forth” into heaven like arrows (Letter 130.20). In the Apophthegmata or Sayings of the Desert Fathers there was a variety of such “arrow prayers”; the name “Jesus” sometimes occurs in them, but enjoys no special prominence.

It is in the writings of Diadochos, bishop of Photike in Northern Greece (mid-5th century), that the Jesus Prayer first emerged as a distinctive spiritual way. Whereas the 4th-century desert fathers used many different “monologic” formulae, Diadochos recommended adherence to a single, unvarying phrase: “Give to your intellect [nous] nothing but the prayer Lord Jesus” (Century 59). He did not say whether other words are to follow this opening invocation. Diadochos adopted from Evagrios of Pontos (346–99) the teaching that inner prayer should take an “apophatic” or “noniconic” form, being free from images, intellectual concepts, and discursive thinking. While Evagrios himself did not suggest any practical method whereby such prayer can be achieved, Diadochos saw this as precisely the function of the Jesus Prayer. The human mind has an intrinsic need for activity, and this can be satisfied by giving it as a task the constant recitation of the words “Lord Jesus”: “Let the intellect continually concentrate on these words within its inner shrine with such intensity that it is not turned aside to any mental images” (Century 59). Thus the Jesus Prayer, as an image-free manner of praying, is not a form of imaginative meditation on specific incidents in the life of Christ, but a means whereby, in the words of Diadochos, we block “all the outlets” of the nous. As we recite the prayer, we are to have a vivid sense of the immediate presence of Christ, but this is to be unaccompanied, so far as possible, by images or intellectual concepts.

In this way, the Jesus Prayer is a prayer in words; but because the words are few and simple, and because the same words are repeated over and over again – because, moreover, the mind of the one who prays is to be stripped of images and thoughts – it is a prayer that leads us through words into silence, initiating us into hesychia or inner stillness of the heart.

The use of the Jesus Prayer seems at first to have been somewhat restricted. It is mentioned by Sinaite authors in the 7th to 9th centuries, such as John Klimakos and Hesychios of Batos. But there are no references to it in Maximos the Confessor (ca. 580–662) or in the authentic works of Symeon the New Theologian (959–1022), although texts relating to it occur in the 11th-century anthology Evergetinos. It comes to greater prominence in the late 13th and 14th centuries, through Athonite writers such as Nikiphoros the Hesychast, Gregory of Sinai, and Gregory Palamas, and through the Constantinopolitan monks Kallistos and Ignatios Xanthopoulos. In these authors there are two important developments:

1 The recitation of the Jesus Prayer is seen as leading to a vision of divine light, which is regarded as identical with the light that shone from Christ at his transfiguration upon Mount Tabor.

2 A psychosomatic technique is recommended when reciting the prayer, which may in fact be more ancient than the 14th century (there are possible allusions in Coptic sources of the 7th-8th centuries). The technique involves three elements: (a) a specific bodily posture (sitting on a low stool, with head and shoulders bowed); (b) regulation of the rhythm of the breathing; (c) inner concentration upon the place of the heart.

There are parallels to all this in Yoga and among the Sufis. But this bodily method is no more than an optional accessory and does not constitute the essence of the Jesus Prayer.

Another external aid is the use of a prayer rope (Greek: komvoschoinion; Russian: tchotki), usually made of knotted cord or wool, although it can be of beads or leather. This is not mentioned in the 14th- century Greek sources, but it can be seen in icons of saints from the 16th and 17th centuries.

The leading figures in the 18th-century hesychast renaissance, such as Nikodimos of the Holy Mountain, greatly valued the Jesus Prayer, and there are many references to it in the Philokalia. From the Kievan period (11th-12th centuries) onwards, it was known and used in Russia. Since the 1920s it has also become familiar in the West, especially through translations of the anonymous 19th-century Russian work The Pilgrim’s Tale (also called The Way of the Pilgrim). Indeed, it may confidently be claimed that the Jesus Prayer is more widely practiced today than ever in the past, alike by monastics and lay people, both Orthodox and non-Orthodox.

SEE ALSO: Desert Fathers and Mothers; Imiaslavie; St. Maximos the Confessor (580–662); Philokalia; Pilgrim, Way of the; Pontike, Evagrios (ca. 345–399); St. Gregory Palamas (1296–1359); St. John Klimakos (ca. 579-ca. 659)

REFERENCES AND SUGGESTED READINGS

Adnes, P. (1974) “Priere de Jesus,” in Dictionnaire de spiritualite vol. 8, cols 1126–50. Paris.

Alfeyev, H. (2007) Le Nom grand et glorieux: la veneration du nom de dieu et la priere de jesus dans la tradition orthodoxe. Paris: Cerf.

Brianchaninov, I. (2006) On the Prayer of Jesus, revd. edn. Boston: New Seeds.

Hausherr, I. (1978) The Name of Jesus. Cistercian Studies Series 44. Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications.

Mainardi, A. (ed.) (2005) La Preghiera di

Gesh nella spiritualita russa del XIX secolo. Magnano: Edizioni Qiqajon/Communita di Bose.

Monk of the Eastern Church [LevGillet] (1987) The Jesus Prayer. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

Ware, K. (1986) The Power of the Name: The Jesus Prayer in Orthodox Spirituality. Fairacres Publication 43. Oxford: SLG Press.

Ware, K. (2003) “The Beginnings of the Jesus Prayer,” in B. Ward and R. Waller (eds.) Joy of Heaven: Springs of Christian Spirituality. London: SPCK, pp. 1–29.

John Bekkos see Lyons, Council of (1274)