Hymnography

DIMITRI CONOMOS

It may be argued that Byzantine hymnody originates from the establishment of the first Christian community: that of Christ and his disciples. Evidence of early Christian hymns can be extracted from the New Testament. Matthew and Mark, describing the Last Supper, report that when Jesus and his followers had finished the meal, and when they had sung a hymn, they went out to the Mount of Olives (Mt. 6.30; Mk. 14.26). This “hymn” may well have been the traditional Passover Hallel (Ps. 112–117). In Colossians 3.16 St. Paul admonishes the new Christian assemblies, saying: “Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly in all wisdom; teaching and admonishing one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing with grace in you heart to the Lord.” Biblical scholarship has now identified a considerable amount of hymnodic material embedded in the text of the New Testament, as for example in Romans 11.33–36, Ephesians 1.3–14, and Revelation 1.5–8.

Subsequent evidence for this tradition may be traced in the writings of the early fathers whose prose texts, using hymnodic techniques, actually follow a practice of Greek literature older than the Christian Scriptures. Poetic homilies prove to be extremely valuable, for they represent the transition from pagan to Christian Greek hymns in prose, and they greatly influence the formation and consolidation of the expressive apparatus of hymnody whose elements of style include simple, lively language, elevated character and manner, striking imagery, deft figures of speech, and so forth. Important examples are the 2nd-century Easter Homily (Peri Pascha) of Melito of Sardis and the Partheneion of Methodios, 4th-century bishop of Olympus. Other early Christian hymns, still used in Orthodox services, are the well-known Phos Hilarion, the Doxology, Only-begotten Son, and the Trisagion.

The acquisition of more detailed information about the development of hymnody in the early Christian centuries is frustrated by a lack of secure evidence. Some early monastic resistance to the chanting of hymns in worship was based on the belief that the practice was detrimental to the soul. Equally decisive was the prohibition of the church, following the legalization of Christianity (312), relating to the employment of hymns in worship because of the fear of non-conformist doctrines. The church was, at this time, on its guard against pagan and heretical hymns, psalmoi idiotikoi (“personal chants”), as the 4th-century Council of Laodicea calls them. Not only was a canon of Scripture identified, but also the performance of hymns, as were found exclusively in church-approved books, was given to ordained clerks. This conservatively motivated exclusion of non-scriptural hymnody, however, proved to be both a shortsighted measure and an extremely dangerous one, because, by restricting the scope of prospective hymnodists, it left the faithful exposed to the charms of an escalating and alluring heretical hymnody. Finally, the Orthodox learned to combat their enemies by using the latter’s own weapons; that is, they composed Orthodox hymns which were built on the same metrical and musical patterns as those of the heterodox. Sozomenos, the church historian, is very clear about this when he speaks of how Ephrem the Syrian wrote his own hymns to weaken the sinister influence of the hymns of the Gnostic poets on the souls of his countrymen. Ironically, the growth of Christian hymnody was promoted by the success that the Gnostic and heretical hymns enjoyed, which attracted many Christians to the services in which they were chanted.

Byzantine hymnody written in the new rhythmic (as opposed to the archaic quantitative) verse may be broadly classified into three genres. The earliest is the troparion, which makes its appearance in the 3rd century. A generic term, troparion designates any stanza of religious poetry. It is also a collective term for several species of hymn in the Byzantine liturgy. The second is the kontakion, a long and elaborate metrical sermon whose history begins in the 6th century. And finally there is the hymn cycle known as the canon, known from the 7th century. Each species continued to be composed and to evolve for many centuries side by side with other forms of religious poetry that gradually developed.

After the 5th century, there are indications that Old Testament psalms and canticles, used as lections in the offices of the burgeoning monastic communities, were assumed in urban worship though in an innovative hymnodic form: newly composed stanzas (later known as stichera), offering poetic commentaries (literary tropes) with unchanging pendant refrains, were inserted between the biblical verses and executed in responsorial fashion by congregational choirs.

Although no music for the early hymns survives, it is generally held that, like their Gregorian counterparts, the Byzantine melodies were unpretentious, generally composed on the rule of one tone to each syllable of the text, to render them suitable for congregational singing. They were familiar to everyone (the melodies were usually transmitted by oral tradition) and consequently did not need to be written down.

The earliest notated chants reflect the characteristics of a widespread oral tradition. Their simple tunes use a restricted stock of musical phrases indicative of each mode; they often divide into sections, each consisting of a pair of lines with the same music, and end with a separate refrain-like line known as the akroteleution. Although the music appears to be rather plain, these verses could be performed in different ways: congregation alone; soloist alone; soloist followed by congregation; congregation singing the akroteleution responsorially; or with melodic elaboration.

The hymns can be grouped according to their subject matter, liturgical position, melodic type, scriptural context, or geographic origin. An anastasimon makes reference to the resurrection and is normally appointed on Sundays; a theotokion honors the Blessed Virgin (and a stavrotheotokion relates to Mary at the foot of the cross); a triadikon is addressed to the Holy Trinity; a doxastikon is sung with the Lesser Doxology;

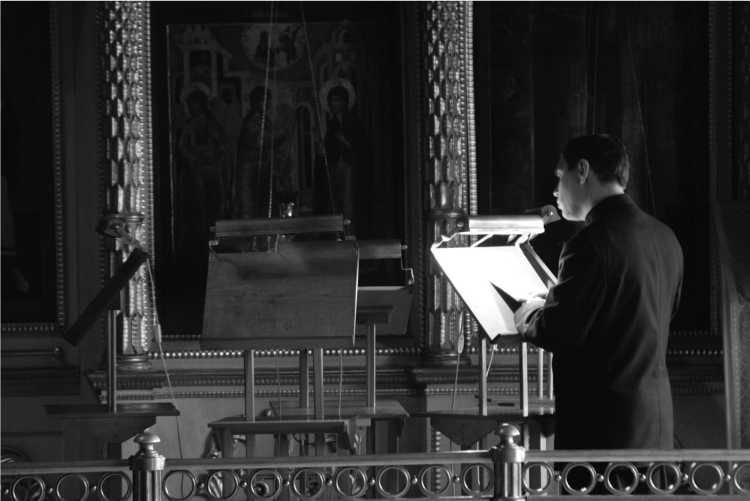

Plate 31 An Orthodox church cantor. Almost all public church services are sung in Orthodox ritual. Photo by John McGuckin

the eisodikon is an introit, while an apolytikion is the dismissal hymn of Vespers; the exaposteilarion develops the theme of Christ as Light of the world and occurs towards the end of Matins; and anatolika hymns originate “from the East»

SEE ALSO: Akathistos; Apolytkion; Cherubi- kon; Ekphonesis; Eothina; Evlogitaria; Exaposteilarion; Heirmologion; Idiomelon; Ode; Troparion

REFERENCES AND SUGGESTED READINGS

Beck, H.-G. (1959) Kirche und theologische

Literatur im byzantinischen Reich. Munich. Conomos, D. (1985) Byzantine Hymnography and Byzantine Chant. Brookline, MA: Holy Cross Orthodox Press.

Follieri, E. (1960–6) Initia hymnorum ecclesiae graecae. Rome: Vatican City.

McGuckin, J. A. (2009) “Poetry and Hymnography (2). The Greek Christian World,” in S. Ashbrook Harvey and D. Hunter (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Mitsakis, K. (1986) Byzantine Hymnographia 1: Apo tin epoche tis Kainis Diathikis eos tin Eikonomachia. Athens.

Szoverffy, J. (1978–9) A Guide to Hymnography: A Classified Bibliography of Texts and Studies. Brookline, MA: Holy Cross Orthodox Press.