Hesychasm

METROPOLITAN KALLISTOS OF DIOKLEIA

The terms “hesychasm” and “hesychast”

are derived from the Greek word hesychia,

meaning “quietness,” “silence,” or “inner stillness.” From the beginning of Christian monasticism, hesychia has been regarded as a primary characteristic of the monk: in the words ofNeilos of Ankyra (d. ca. 430), “It is impossible for muddy water to grow clear if it is constantly stirred up; and it is impossible to become a monk without hesychia” (Exhortation to Monks, PG 79: 1236B). The essence of hesychasm is summed up in the command given by God to the desert father Arsenios (d. 449): “Arsenios, flee, keep silent, be still [hesychaze], for these are the roots of stillness” (Apophthegmata, alphabetical collection, Arsenios 2). The term “hesychasm” has sometimes been rendered as “quietism,” but this is potentially misleading, since the Quietist movement in the 17th-century West is significantly different from the hesychast tradition in the East.

In early sources (4th-6th centuries), hesychia sometimes indicates the solitary life; a hesychast is a hermit or recluse, as contrasted with a monk dwelling in a cenobium or organized community. More commonly, however, especially in later sources, hesychia is given an interiorized and spiritual sense, and denotes silence of the heart. It usually signifies the quest for union with God through “apophatic” or “non-iconic” prayer, that is to say, prayer that is free from images and discursive thinking. From the 5th century onwards, one of the chief means for attaining such hesychast prayer has been the Invocation of the Holy Name or Jesus Prayer. By the 14th century, if not before, the Jesus Prayer was often accompanied by a psychosomatic technique, involving in particular control of the breathing.

ORIGINS

A decisive role in the emergence of hesychasm was played by Evagrios Pontike (346–99). Taking up a scheme devised by

Origen (ca. 185-ca. 254), Evagrios divided the spiritual life into three stages or levels:

1 Praxis or praktike, the “active life,” i.e., the struggle to eliminate evil thoughts (logismoi) and to acquire the virtues. This begins with repentance (metanoia) and leads eventually to “dispassion” or freedom from the passions (apatheia), which in its turn is closely linked to love (agape).

2 Physike, “natural contemplation” or the contemplation of God in nature. This includes contemplation of the angelic orders.

3 Theologia: the contemplation of God in himself, on a level above creation.

4 Prayer, for Evagrios, is above all an activity of the intellect (nous). In its highest expression, prayer is “pure” or image-free: “When you are praying,” writes Evagrios, “do not shape within yourself any image of the Deity, and do not let your intellect be stamped with the impress of any form; but approach the Immaterial in an immaterial manner.... Prayer is a putting-away of thoughts” (On Prayer 66 67, 70 71). Pure prayer is often accompanied by a vision of light. This exists at two levels. First, the hesychast may behold “the light of the intellect”; this is evidently a created light, an experience of the self as totally luminous. Then, at a more exalted level, he or she may behold the “light of the Holy Trinity,” that is to say, a light that is divine and uncreated.

Plate 27 Monastic cells of the monks at the Sinaya Monastery, Romania, once a dependency of Mount Sinai. Photo by John McGuckin.

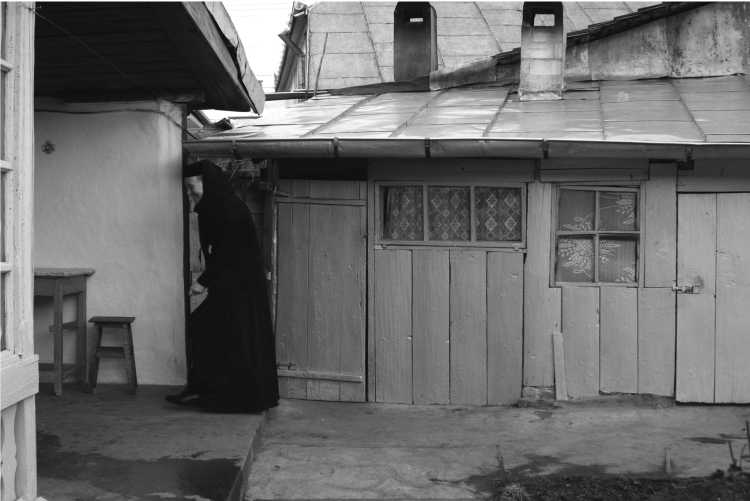

Plate 28 A hermitage in the complex of buildings at the Romanian women’s monastery at Varatec. Several thousand nuns live and pray at this site. Photo by John McGuckin

A somewhat different approach to prayer is to be found in the Macarian Homilies (? late 4th century). Great emphasis is placed by the Homilies upon direct experience of the Holy Spirit. The Homilies do not differentiate clearly between advancing stages in prayer, nor do they speak of the need to lay aside images and thoughts. They treat prayer as an activity not primarily of the intellect (nous), but of the heart (kardia). Yet the contrast between Evagrios and the Macarian Homilies should not be exaggerated. Nous in Evagrios does not mean the reasoning brain (dianoia), but the faculty whereby we apprehend truth intuitively, through an act of inner vision, a sudden flash of insight. On the other hand, kardia in the Homilies does not signify only or primarily the emotions and feelings, but it denotes the moral and spiritual center of the total human person; the nous is regarded as dwelling within the heart, and in the Homilies there is no head/heart contrast. In common with Evagrios, the Macarian Homilies speak of a vision of light, which is clearly understood as uncreated and divine.

Both Evagrios and the Macarian Homilies belonged in this way to the tradition of “light mysticism,” as also did Gregory of Nazianzos (ca. 329-ca. 389). None of them assigned a significant place to the symbol of divine darkness. The Jewish writer Philo (ca. 20 BCE-ca. ce 50), however, and after him the Christian author Clement of Alexandria (ca. 150-ca. 215), both made use of the notion of mystical darkness. Drawing on them, Gregory of Nyssa (ca. 330-ca. 395) assigned a central place to divine darkness in his treatise The Life of Moses. Here he distinguished three stages in the spiritual journey, which differ markedly from those in the triadic scheme in Evagrios:

1 Moses, who is treated as a paradigm of mystical theology, was first granted a vision of light in the burning bush (Ex. 3). For Gregory, this is not an ordinary physical radiance, but a light that is divine.

2 After this came a vision of mingled light and darkness (Ex. 13.21, the pillar of cloud and fire).

3 Moses then met God in the “thick darkness” of Sinai (Ex. 20.21), signifying the divine incomprehensibility. On the basis of this encounter with God in darkness,

Gregory propounded a series of paradoxes: the true vision of God is nonvision; the true contemplation of God consists in the realization that he cannot be contemplated; the true knowledge of God is unknowing. But Gregory also spoke of the darkness of Sinai as “luminous,” for the darkness is not a symbol of separation but of union with God in love.

In this way, Gregory reversed the usual sequence: the spiritual journey is not from darkness to light but from light to darkness. After the ascent of Sinai, there is a fourth and further stage, when Moses was hidden in the crevice of a rock, and saw not God’s face but his back (Ex. 33.20–23). Gregory interpreted this to mean that the spiritual journey involves perpetual progress, an unending “reaching forward” or epektasis (Phil. 3.13–14). Even in heaven the saints never cease the advance from “glory to glory” (2Cor. 3.18). The essence ofperfec- tion consists in the fact that one never becomes perfect; every endpoint is but a new beginning. Yet to follow God is to be united with him, and to seek him endlessly is precisely to find him.

Diadochos of Photike (mid-5th century) took up the teaching of Evagrios on “pure” prayer, and he offered a practical method whereby this image-free prayer may be attained: through the invocation “Lord Jesus,” that is to say, through what later became known as the Jesus Prayer. In common with Evagrios, Diadochos believed that inner prayer leads to a vision oflight: first, an experience of the light of the nous, and then an experience of divine light. But this vision of light is aneideos, without form or shape; it is an experience of pure luminosity.

The unknown author of the writings attributed to Dionysius the Areopagite (ca. 500) followed Clement and Gregory of Nyssa in interpreting the mystical ascent as an entry into the darkness of Sinai. At that same time, he (or she) insisted upon a “coincidence of opposites”; at the divine level there is a convergence between the symbols of light and darkness. Just as Gregory of Nyssa described the darkness as luminous, so Dionysius wrote: “The divine darkness is the Light to which no one can approach” (Letter 5; cf. 1Tim. 6.16). Dionysius proposed a threefold scheme of the spiritual life: purification, illumination, union. While this Dionysian scheme was widely adopted in the Latin West, it is the somewhat different Evagrian scheme that prevailed on the whole in the Greek East, most notably in Maximos the Confessor (ca. 580–662). Some writers, such as Niketas Stethatos (11th century), combined the two schemes together.

MIDDLE BYZANTINE PERIOD

John Klimakos (ca. 570-ca. 649), abbot of Sinai, in Step 27 of his Ladder of Divine Ascent, provided a classic definition of what it is to be a hesychast: “The hesychast is one who strives to confine his incorporeal self within the house of the body, paradoxical though this may sound.” Thus hesychasm is an entry within oneself, a discovery of the indwelling Christ within the secret sanctuary of the heart. Hesychasm, Klimakos continued, involves nepsis, “wakefulness” or “vigilance”: the hesychast is one who says, “I sleep, but my heart is awake” (Song of Songs 5.2). Hesychia is in this way a continual awareness of God’s presence: as Klimakos put it, “Hesychia is worshipping God unceasingly and waiting upon him.” This continual awareness is maintained through the Jesus Prayer: “Let the remembrance of Jesus be present with your every breath. Then indeed you will appreciate the value of hesychia.” The hesychast seeks union with God on a level free of mental images and discursive thinking. Adapting the words of Evagrios, Klimakos wrote: “Hesychia is a putting- away of thoughts.” From all this it is evident that, for Klimakos, hesychia meant not primarily the life of a hermit but a way of inner prayer.

Symeon the New Theologian (949–1022) revived the emphasis placed by the Macarian Homilies upon conscious experience:

Do not say, It is impossible to receive the Holy Spirit.

Do not say, It is possible to be saved without him.

Do not say, then, that one can possess him without knowing it

(Hymn 27.125–7)

The conscious experience ofthe Spirit takes the form of a vision of the light of Christ (for Christ and the Spirit are inseparable). Symeon affirmed clearly and definitely that this light is not physical and created, but non-material and divine: “Your Light, my God, is you yourself” (Hymn 45.6). The divine light has a transforming effect upon the one who beholds it, so that he himself becomes light. Although Symeon has left accounts of how Christ spoke to him out of the light, it seems that he did not actually see the face of Christ in the light. As with Diadochos, the vision is one of pure luminosity, without shape or form (although in one vision Symeon saw his spiritual father standing close to the light).

HESYCHAST CONTROVERSY

In the last years of the 13th century an Athonite monk, Nikiphoros the Hesychast, wrote a short but influential treatise On Watchfulness and the Guarding of the Heart. Here he spoke of “returning” or “entering” into oneself and “seeking the treasure within the heart.” To facilitate this, he suggested that the recitation of the Jesus Prayer should be accompanied by a psychosomatic technique, involving the descent of the intellect, along with the breath, into the heart.

A similar technique was recommended by another Athonite monk in the following generation, Gregory of Sinai (d. 1346). Gregory set the Jesus Prayer in a sacramental context, seeing it as a means whereby we rediscover the grace received in baptism: prayer, he said, is nothing else than “the making manifest of baptism” (On Commandments and Doctrines 113). Using Eucharistic symbolism, he also described how the hesychast through prayer enters “the inner sanctuary,” where he “celebrates the triadic liturgy,” “offering up the Lamb of God upon the altar of the soul and partaking of him in communion” (On Commandments and Doctrines 43, 112).

In 1337–8 the Athonite tradition of hesychast prayer was attacked by a learned Greek from Southern Italy, Barlaam the Calabrian (ca. 1290–1348). It has been suggested that he was influenced bywestern Nominalism, but this is unlikely; he was basically a Neoplatonist. He argued that the light seen by the monks in prayer was not divine but created, an illusion conjured up by their own fantasy; and he criticized the physical technique as superstitious and grossly materialistic.

The defense of the hesychasts was undertaken by Gregory Palamas (1296–1359), a monk of Athos who became at the end of his life archbishop of Thessaloniki. According to Palamas, the vision that the monks beheld was not created and physical, but was identical with the divine and uncreated light that shone from Christ at his transfiguration on Tabor. Distinguishing, however, between the essence and the energies of God, he maintained that this divine light is not a vision of God’s essence, which transcends all participation and remains for ever unknowable, but it is a manifestation of his eternal energies. These energies, however, so far from being a created intermediary between God and humankind, are nothing less than God himself in action: “Each power and energy is God himself” (Letter to Gabras); “God is wholly present in each of his energies” (Triads 3.2.7). This teaching of Palamas concerning the divine light was endorsed by three councils of Constantinople (1341, 1347, 1351), which, although they were not ecumenical, have come to be accepted by the Orthodox Church as a whole.

Palamas also defended the physical technique used with the Jesus Prayer. He did not consider it an essential part of the prayer, but saw it as an optional aid, suited chiefly for beginners; yet in his view it is theologically defensible. Since the human person is an integral unity of soul and body, the latter should play its part in the work of prayer. Here Palamas upheld a holistic view of the human person. Christ, through his incarnation, “has made the flesh an inexhaustible source of sanctification” (Homily 16); and so “the body is deified along with the soul” (Triads 1.3.37, quoting Maximos the Confessor).

An excellent summary of hesychast teaching was provided, towards the end of the 14th century, by the Constantinopolitan monks Kallistos and Ignatios Xanthopoulos in their treatise On the Life of Stillness and Solitude. In common with Gregory of Sinai, they established a close link between the sacraments and the inner prayer of the hesychast. The aim of the spiritual life is the ever-increasing “manifestation” of baptism (§4); the reception of holy communion by the hesychast should be “continual” and if possible daily (§§91–2).

In this way, for writers such as Gregory of Sinai and the Xanthopouloi, the recitation of the Jesus Prayer deepens and enriches the sacramental life, but does not by any means replace it. It is important to recognize that throughout the history of hesychasm, from the 4th century onwards, those who wrote about inner contemplation and the Jesus Prayer took it for granted that anyone pursuing the spiritual way would be an active member of the ecclesial community, regularly participating in the sacraments of confession and holy communion. If hesychast writers do not always speak of this explicitly, it is because they assume it as axiomatic.

Another basic presupposition in hesychast teaching is the need for spiritual direction. The hesychast should, if possible, be under the personal guidance of an experienced elder (Greek geron; Russian starets). This was emphasized, at the first beginnings of monasticism, by Antony of Egypt (251–356): “If possible, for every step that a monk takes, for every drop of water that he drinks in his cell, he should entrust the decision to the elders, to avoid making some mistake in what he does” (Apophthegmata, alphabetical collection, Antony 38). “Above all else,” Kallistos and Ignatios Xanthopoulos insisted, “search diligently for an unerring guide and teacher” (§14).

HESYCHAST RENAISSANCE

The hesychast tradition of prayer, as taught by Symeon the New Theologian, Gregory of Sinai, and Gregory Palamas, was reaffirmed in the 18th century by the movement of the Greek Kollyvades, especially through the publication in 1782 of the vast collection of ascetic and mystical texts entitled the Philokalia. Edited by Makarios of Corinth (1731–1805) and Nikodemos of the Holy Mountain (1749–1809), this constitutes a veritable encyclopedia of hesychasm.

In Russia, the first detailed account of Hesychast teachings was provided by Nil

Sorskii (ca. 1433–1508), who during a stay on Athos had gained a first-hand knowledge of the practice of the Jesus Prayer, and who was particularly influenced by Gregory of Sinai. The Slavonic translation of the Philokalia, made by Paisy Velichkovsky (1722–94) and published in 1793, proved widely influential in 19th-century Russia, and was used by Seraphim of Sarov (1759–1833) and by the elders of the Optino hermitage. Hesychast teaching was likewise disseminated by Ignatius Brianchaninov (1807–67) and Theophan the Recluse (1815–94); the latter prepared a greatly expanded Russian translation of the Philokalia.

During the 20th century hesychasm underwent a further renewal, both in Greece and in the western world. It remains today very much a living tradition. In the second half of the century, particularly through the research of John Meyendorff (1926–92), the theology of Gregory Palamas came to be far better understood. At the same time, hesychast writings reached western readers through translations of the Philokalia. In the past hesychasm was chiefly propagated in certain Orthodox monastic centers, but today it has come to be practiced by many lay Christians, not only Orthodox but nonOrthodox. The spread of hesychasm among the laity is something that its 14th-century protagonists would have applauded. Gregory of Sinai sent his disciples out from the Holy Mountain to the city of Thessaloniki, to act as guides to lay people; and Gregory Palamas, in a dispute with a certain monk Job, insisted that Paul’s words, “Pray without ceasing” (1Thes. 5.17), are addressed not just to monastics but to every Christian without exception. Hesychasm is in principle a universal way.

SEE ALSO: Contemporary Orthodox Theology; Elder (Starets); Jesus Prayer; Kollyvadic Fathers; Optina; Philokalia·; Pilgrim, Way of the, Pontike, Evagrios (ca. 345–399); St. Gregory Palamas (1296–1359); St. Ignatius Brianchaninov (1807–1867); St. Nikodemos the Hagiorite (1749–1809); St. Paisy Velichovsky (1722–1794); St. Seraphim of Sarov (1759–1833); St. Symeon the New Theologian (949–1022); St. Theophan (Govorov) the Recluse (1815–1894)

REFERENCES AND SUGGESTED READINGS

Adnes, P. (1968) “Hesychasme,” in Dictionnaire de spiritualite 7: cols. 381–99. Paris: Cerf.

Alfeyev, H. (2000) St. Symeon the New Theologian and Orthodox Tradition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hausherr, I. (1956) “L’hesychasme, Etude de spiritualite,” Orientalia Christiana Periodica 22: 5–40, 247–85; reprinted in I. Hausherr (1966) Hesychasme et priere, Orientalia Christiana Analecta 176. Rome: Pont. Institutum Orientalium Studiorum, pp. 163–237.

Horujy, S. S. (2004) Hesychasm: An Annotated Bibliography. Moscow: Russian Orthodox Church.

Lossky, V. (1957) The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church. London: James Clarke.

Lossky, V. (1963) The Vision of God. London: Faith Press.

Louth, A. (1981) The Origins of the Christian Mystical Tradition. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

McGuckin, J. A. (2001) Standing in God’s Holy Fire: The Spiritual Tradition of Byzantium. London: Darton, Longman and Todd.

Meyendorff, J. (1964) A Study of Gregory Palamas. London: Faith Press.

Meyendorff, J. (1974) St. Gregory Palamas and Orthodox Spirituality. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

Meyendorff, J. (1983) “Is ‘Hesychasm’ the Right Word? Remarks on Religious Ideology in the Fourteenth Century,” in C. Mango and O. Pritsak (eds.) Okeanos: Essays presented to I. Sevcenko on his Sixtieth Birthday. Harvard Ukrainian Studies 7. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, pp. 447–57.

Ware, K. (2000) The Inner Kingdom. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, pp. 89–110.