Episcopacy

PHILIP ZYMARIS

The episcopacy is the highest rank of holy orders (priesthood) in the Orthodox ecclesiastical hierarchy, based on the tradition of the New Testament and Canon Law.

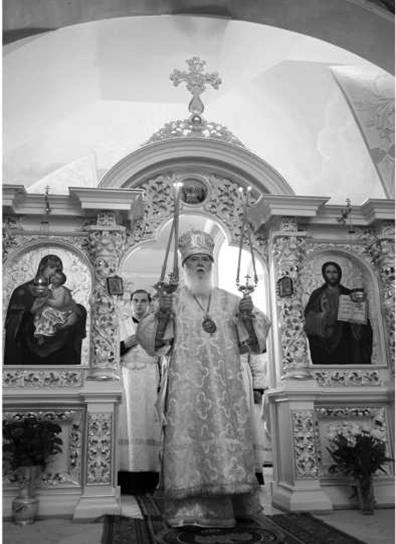

Plate 20 Ukrainian bishop giving the blessing at the divine liturgy with the Dikeri and Trikeri candlesticks, standing in front of the iconostasis. Photo © Joyfull/Shutterstock.

tradition of the New Testament and Canon Law. The earliest historical reference to the episcopacy is to be found in the New Testament. Although the distinction between presbyteros (elder) and episkopos (overseer- bishop) was initially vague (cf. Phil. 1.1; Acts 20.28), the latter crystallized to denote the specific ministry of the president of the Eucharistic assembly. In this capacity the bishop presides as icon of Christ and successor of the apostles (see Ignatios of Antioch, To the Smyrneans 8.1–2).

The acceptance of Christianity by the Roman Empire led to changes in the administrative structure of the episcopacy. Whereas in New Testament times St. Paul simply refers to one bishop in each city (Zizioulas 2001: 47f.), the administrative structure of the church later coincided with the civil organization of the empire. This allowed the development of the metropolitan system of church government where bishops of a group of provinces would refer administratively to the bishop of the main city (meter-polis, “mother city,” hence the metropolitan) of the wider region. The metropolitan would preside over a synod composed of bishops from the provinces under his ecclesiastical authority. According to the 34th Apostolic Canon the “many,” i.e., the bishops of a region, could do nothing without the “first,” i.e., the metropolitan, and the metropolitan could do nothing without the many. At every level of episcopal activity this became the basis for the teaching on canonical primacy in the Orthodox Church; namely, the first who acts as coordinator for the many but who is not an overlord above the others. The later development in the West of the papal primacy as a jurisdictional superiority was a significant departure from this notion.

The subsequent appearance of the pentarchy developed along these same lines. Eventually, a group of main cities (metropoleis) would belong administratively to an even more significant city. The metropolitans of the significant five cities of Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem were eventually given the title of patriarch. These patriarchs would preside over a synod made up of the metropolitans from the provinces under the civil authority of the aforementioned five cities. These patriarchates were also organized according to the tenets of primacy. The pope of Rome originally fulfilled this role of “first among equals.” The patriarch of Constantinople presently fulfills this role for the Orthodox subsequent to the schism of 1054, although there is not full agreement on this issue in contemporary Orthodox practice. This is because new patriarchates have been founded since then, as well as other autocephalous churches headed by metropolitans or archbishops. In theory all these churches relate to each other according to the aforementioned tenets of primacy. In general, metropolitans were considered to rank higher in the episcopal lists than archbishops, but this is not always the case in contemporary practice.

As the focal point of unity for the local church, the bishops collectively express the consciousness of their local churches and promulgate the canon law of the church in the context ofthe synods ofthe church. This conciliar role of the episcopacy serves as a tangible link between the local churches and the one “Church in the World” (Zizioulas 2001: 125f.).

This link between the local and universal church inherent in the episcopacy is also evident in the service of ordination to the episcopate. In this service the connection of the ordained to a specific city is emphasized, yet canonical practice also links this local church to all other local churches. Thus, according to the Council of Nicea (325), episcopal ordinations require the participation of at least three other bishops (Canon 4).

In contemporary practice the connection with a specific community implicit in the ordination service is sometimes overshadowed by administrative concerns. Thus, a bishop may be “titular,” i.e., attached at ordination to a city no longer in existence. Such bishops are distinguished from bishops who pastor a living community, but they are also distinguished from so- called en energeia (acting) bishops, i.e., bishops who possess an existing see but are unable to serve there due to historical circumstances. Most of the metropolitans serving at the ecumenical patriarchate today fall into this category because the cities they preside over no longer have Christian populations to pastor. For this reason the ecumenical patriarchate is governed by the so-called resident (endemousa) synod, which is composed of metropolitans possessing titles of various cities but residing in Constantinople.

The New Testament and the canonical tradition of the church offer clear prescriptions regarding the character of candidates for the episcopacy. They are to be of upright character (Canon 10 of Sardica), experienced in the faith (Canon 2 of the First Council) and of a minimum age of 35. They are also to be proven as good managers of the affairs of their families (Tit. 1.6–9; 1Tim 3.1–13; 3rd Canon of Sixth Council), a prescript that became symbolically exegeted after the 4th century when celibacy was later required of bishop-candidates. Absolute monogamy was also required of all candidates. However, in Byzantine practice, by the 7th century most episcopal candidates were already taken only from the celibate (but not necessarily monastic) clergy (Kotsonis 1964: 784).

In contemporary practice the primarily Eucharistic, pastoral roles of the episcopacy have been slightly overshadowed by increased administrative duties. This is in part due to the precedent set during the Ottoman era in the East. During this period, together with their ecclesiastical duties bishops were compelled to assume administrative roles for the sake of their people according to the Ottoman millet system.

SEE ALSO: Chorepiscopos; Deacon; Eucharist; Ordination; Priesthood; Vestments

REFERENCES AND SUGGESTED READINGS

Clapsis, E. (1985) “The Sacramentality of

Ordination and Apostolic Succession: An

Orthodox Ecumenical View,” Greek Orthodox

Theological Review 30, 4: 421–32.

Kotsonis, I. (1964) “Episkopos,” in Threskeutike kai ethike egkyklopaideia, vol. 5. Athens: A. Martinos, pp. 782–78.

Zizioulas, J. (1980) “Episkope and Episkopos in the Early Church: A Brief Survey of the Evidence,” in Episkope and episcopate in ecumenical perspective. Faith and order Paper 102. Geneva: World Council of Churches, pp. 30–42.

Zizioulas, J. (1985) “The Bishop in the Theological Doctrine of the Orthodox Church,” in R. Potz (ed.) Kanon 7: 23–35.

Zizioulas, J. (2001) Eucharist, Bishop, Church, trans. E. Theokritoff. Brookline, MA: Holy Cross Orthodox Press.